Can a vegetarian lunch reduce the carbon footprint of our event?

At TEDxTUM, we try hard to improve our event every year. In the year of Fridays for Future, this might be a bit of a cliche – but 2019, we did so by focusing a lot on sustainability.

Next to cutting out all single-use plastic bottles, this included going full-on vegetarian. For the past years, we have offered our attendees the choice between a chicken and a vegan wrap (which in 2018 led to a share of 80% chicken and 20% vegan wraps), in 2019 – we chose for them by only offering vegetarian burritos.

However, sustainability is a complicated topic and who even knows what steps to take anymore? Is vegetarian automatically better? To put some numbers on the issue, the small but mighty Burrito-Task-Force assembled and tackled the question of just how much CO2 [1] emissions we could be cutting with this step.

How to identify how much CO2 emissions we were saving

The first step was to get in contact with our Munich-based burrito supplier and collect as much information as we could about what ingredients exactly we had ordered and where they were coming from. Second, what else to do but completely mess up your kitchen and dissect the burrito (see pic below) to figure out just how much of each ingredient would be in there. And then of course, third, dive deep into the internet rabbit-hole and find out everything you can about the carbon footprint of every ingredient.

Easy, right?

Well… no: The amount of CO2 emitted to produce, for instance, one kg of tomatoes varies between 0.3 kg for local production outside and 9.3 kg for production in a heated greenhouse. That’s a factor of more than 30!

So, our next step had to be making reasonable assumptions about a lot of things. Of course, this meant we wouldn’t be able to come up with a 100% accurate number, but then again: we figured as much when we tried to get single grains of rice away from the onion. Fortunately enough, CO2 is an increasingly hot topic (pun intended), and we could benefit from a lot of previous research. So, finally, we ended up with some numbers we were happy to share with our attendees at the event.

Summarising our results

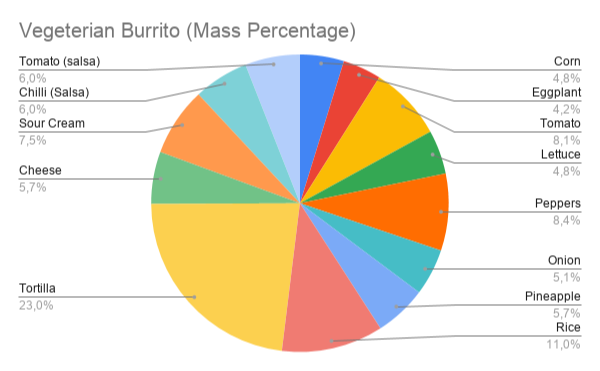

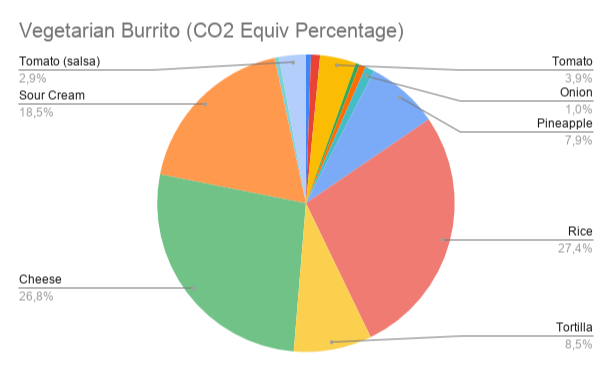

First of all, we created a nice overview on what ingredient contributes how much to the overall impact. On the left, we have a breakdown of our veggie burritos by mass, on the right by emissions. While we kind of expected the huge impact of the two dairy products, especially the amount of emissions attributable to the rice surprised us all. Turns out, flooding the ground when cultivating rice releases microorganisms, which in turn produce quite a bit of methane.

Compared to the 2018 80/20 split between chicken and vegetarian burritos, we were able to cut our emissions by one third. The production of the ingredients of a chicken burrito emits around 1.5 times the amount of CO2 a veggie burrito does (Tangentially related: One beef burrito is equivalent to 5.4 veggie burritos when it comes to greenhouse gases). Scaled to all 700 burritos we ordered this year, this roughly equals an economy flight from Munich to Frankfurt (a distance of 300 km / 190 mi as the crow flies).

Is that a lot? Was it worth the cut? Everybody has to decide for themself obviously. Yet, when we asked our event-attendees the same questions it turned out: In general, people expected about the same or even higher CO2 savings.

For us, this project provided a fascinating glimpse into the variables one has to take into account when trying to judge whether something is “sustainable” and we hope we could share some of the things we learnt with our attendees. While the impact of switching to a vegetarian might have been lower than expected, it was also a very easy step to take. And by raising the attention for a careful approach towards sustainability, we hopefully got the whole team on board to try more and new steps to an even more sustainable 2020 event. One small burrito at a time.

[1] No write up is complete without a footnote, so here we go: Whenever we say CO₂ emissions, we really mean CO₂ equivalent, which does not only include CO₂ but various other greenhouse gases as well. For these, an amount of equivalent CO₂ is calculated based on how much they impact the climate. Another caveat: We completely ignored usage of other resources (say water), which would be a whole other story.